To begin with, the Ghent Altarpiece used to be displayed in the Vijd chapel, the private chapel of Joos Vijd and Elisabeth Borluut, who had commissioned this piece of art. It was mostly them and their family who got to see the altarpiece. We don’t know whether or not other Ghent residents were allowed to see it, but proof of donations can be found in the church council’s accounts. These donations could be considered as a kind of admission ticket. However, this system was probably only available to special invitees, not to common people.

Furthermore, polyptychs such as the Ghent Altarpiece usually remained closed. We suspect that the panels were only opened on Sundays and public holidays, and not at all during Lent. A document from 1585 was preserved in which it was decided to open the polyptych only four times a year, probably because the side panels had sagged under their weight. So, even if we don’t know exactly, this does give an idea of how exceptional it was to have the polyptych open.

Van Eyck must have been obsessed with observing the incidence of light on certain materials. And he not only observed it, he also managed to capture it in his paintings.

Making the blind see again

Finally, and this is the most fundamental difference, 15th-century Ghentians lived in an entirely different world. The visual culture we know today didn’t exist. There were no photographs of course, but hardly any paintings either. Even graphic art only emerged decades later in the form of printed books and engravings in loose prints. The only images known to the 1432 public were occasional paintings in churches or tapestries in important public buildings.

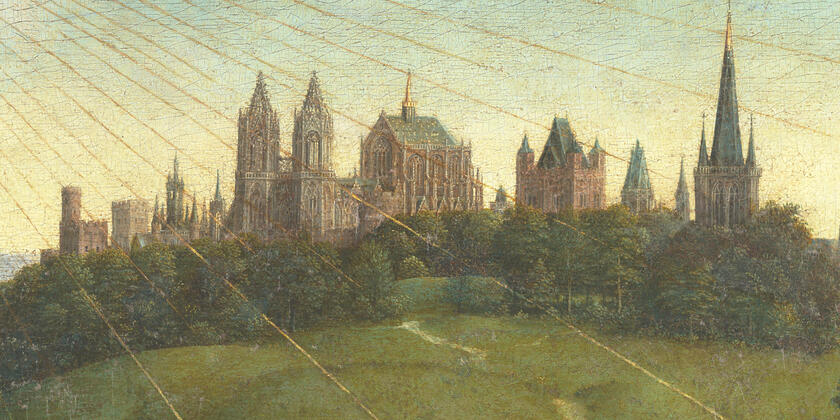

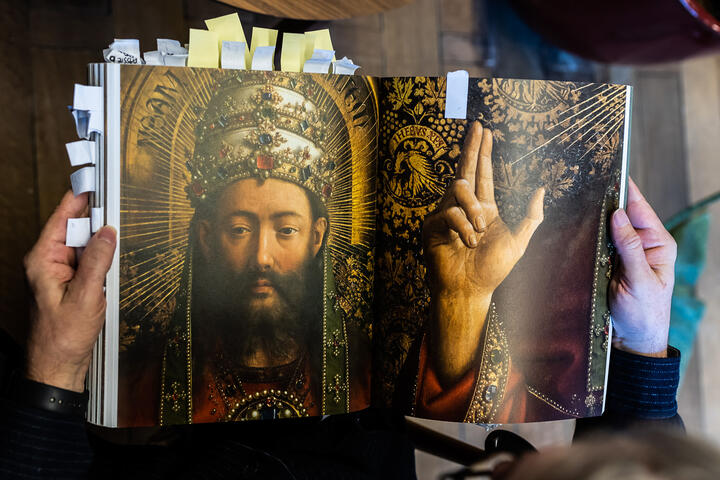

Imagine seeing the Ghent Altarpiece through the eyes of people of that time. The exterior panels are impressive, yet sober in terms of subject and use of colour. When the polyptych opens, the splendour of colour is revealed. Suddenly, you see everything: heavenly Jerusalem with Christ and the saints. It must have felt like a revelation. As if you were born blind and you can suddenly see. It may be an extreme comparison, but this was the impact visual art had on people in the 15th century.

I am convinced that Van Eyck wanted to understand visual perception to get closer to the essence of Creation. The real mystery is how he did this. I think it’s fascinating, as it seems impossible to do in his time. But seeing is believing.

The optical revolution

It’s the fate of all great works of art that anecdotes sometimes take over. Or the imagination. No story is too far-fetched. Think for example of the nonsense that the woman depicted in the Mona Lisa is actually a man. Professionals find it frustrating at times to see that crazy theories receive more attention than scientific insights. The most ridiculous rumours were also spread about the Ghent Altarpiece.

All this actually distracts us from the essence. And the essence is that Van Eyck’s painting marked a revolution. It was a technical revolution, because he perfected the oil painting technique, but it was especially a revolution because of his vision of reality. As a result, he changed the course of painting and his influence can still be felt today. Van Eyck saw and painted reality in a way that no-one else had done before him.

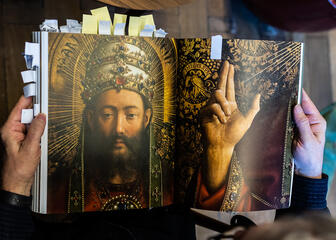

De Visione Dei: face to face with God

The Italians were already well aware of perspective with vanishing points at the time. It was nothing new. Much had also been written about optics. Alhazen’s ancient Arabic writings were revised by British scholars in the 13th century. Physical phenomena, such as reflection and refraction of light, were given a metaphysical dimension. At the end of times, we would allegedly be able to see things without distractions and be face to face with God.

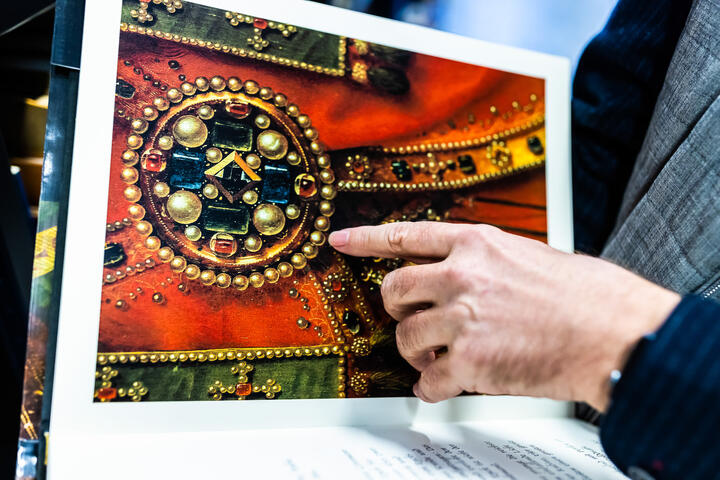

I believe that this is what Van Eyck was aiming for. To get closer to God through extreme perception. The theology behind this idea is complex, but just look at an example in the Ghent Altarpiece: the splashing droplets in the fountain. I once had a slow-motion video made of a droplet falling into water: it’s an intricate game of concentric circles, a round droplet bounces up from the surface and falls down a second time. Today, we have an iPhone with slo-mo to make such videos. Van Eyck simply painted it.

The mystery remains

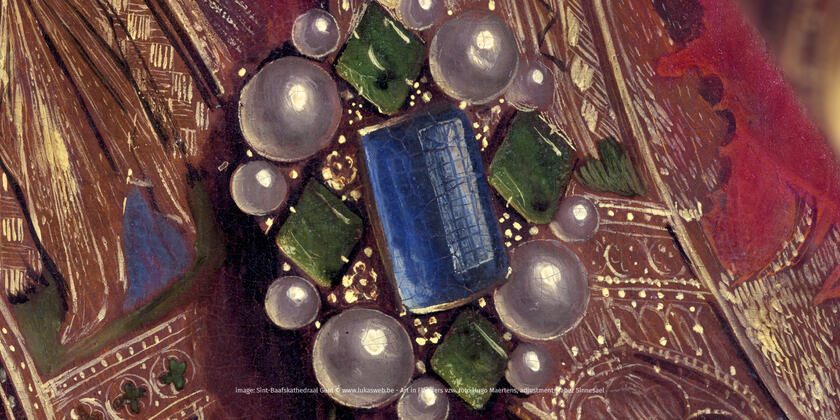

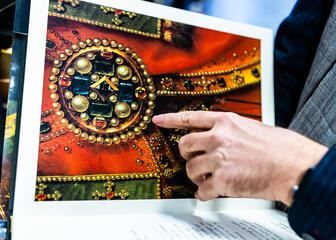

When I show someone the Ghent Altarpiece for the first time, I try to convey my love for the work by asking them the following question: how on earth did this man manage to master perception like that? Van Eyck must have been obsessed with observing the incidence of light on certain materials. And he not only observed it, he also managed to capture it in his paintings. Others tried to achieve the same effect, but he succeeded.

The incidence of light is exactly right for each of the thousands of pearls in the painting, even the reflection of the pearls in other pearls is accurately painted. In modern days, we use 3D simulations and computer models to mimic this effect. I am convinced that Van Eyck wanted to understand visual perception to get closer to the essence of Creation. The real mystery is how he did this. I think it’s fascinating, as it seems impossible to do in his time. But seeing is believing.

Maximiliaan Martens

Maximiliaan Martens is professor of Art History at Ghent University and is a world-renowned expert on Van Eyck. Since 2010, he has been heavily involved in the restoration of the Ghent Altarpiece and the expo Van Eyck. An Optical Revolution. He is still fascinated by the topic that interested him in his student days: how can technology and scientific research help us shed new light on the old masters?