1566: a close escape from the Great Iconoclasm

For the first century after its unveiling in 1432, the Ghent Altarpiece enjoyed a relatively quiet existence. The Great Iconoclasm of 1566 changed that around drastically, marking the beginning of the altarpiece’s stormy history that would only wind down in 2020.

In the mid-16th century, the official religion in Ghent changed from Catholicism to Calvinism. The Calvinists were strongly opposed to the veneration of statues of saints, and saw the Ghent Altarpiece as the pinnacle of Catholic degeneracy. During the devastating Iconoclasm of 1566, whereby countless church interiors were destroyed, a furious mob set its sights on the altarpiece in St Bavo's Cathedral. However, once the crowd managed to break open the cathedral doors, what they found was the Altarpiece had disappeared… The Catholic guardians had winched the masterpiece panel by panel up into the bell tower for safekeeping. A hazardous but effective rescue operation of an irreplaceable piece of world heritage!

1566-1584: under lock and key at the town hall

The Ghent Altarpiece escaped destruction during the Great Iconoclasm of 1566 by the skin of its teeth. The Catholics were not taking any chances sitting around waiting for the Calvinists to discover the hiding place of the polyptych. So they decided to move the work to the stronghold that was town hall. There it remained under lock and key until Catholicism was reinstated in Ghent in 1584. The Ghent Altarpiece was returned to its original location in the Vijd chapel of St Bavo's Cathedral, where it would remain undisturbed for decades to come. Until 1781…

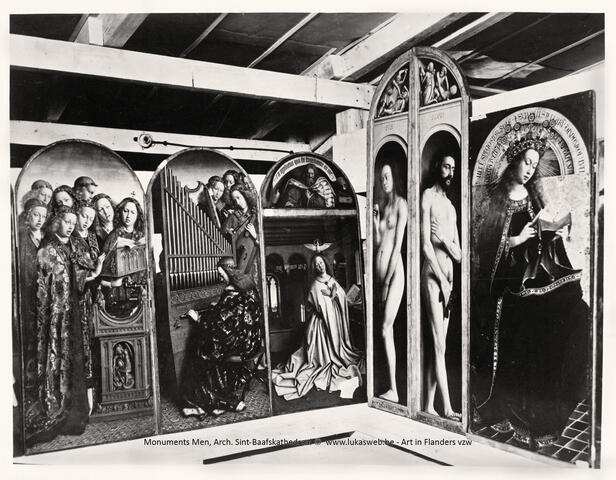

1781: Joseph II the prude vs. Adam and Eve the nude

In 1781, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire Joseph II graced the city of Ghent with his appearance. He had journeyed to the city among others to gaze upon the world-famous Ghent Altarpiece. However, when he set eyes on the work, he was shocked to find the naked portrayal of Adam and Eve. In his mind, the nudity was unnecessary and even pornographic. To avoid any conflict with the emperor, the then-mayor of Ghent had the panels with Adam and Eve removed and stored in the cathedral’s archives.

1794: by horse and cart to Paris

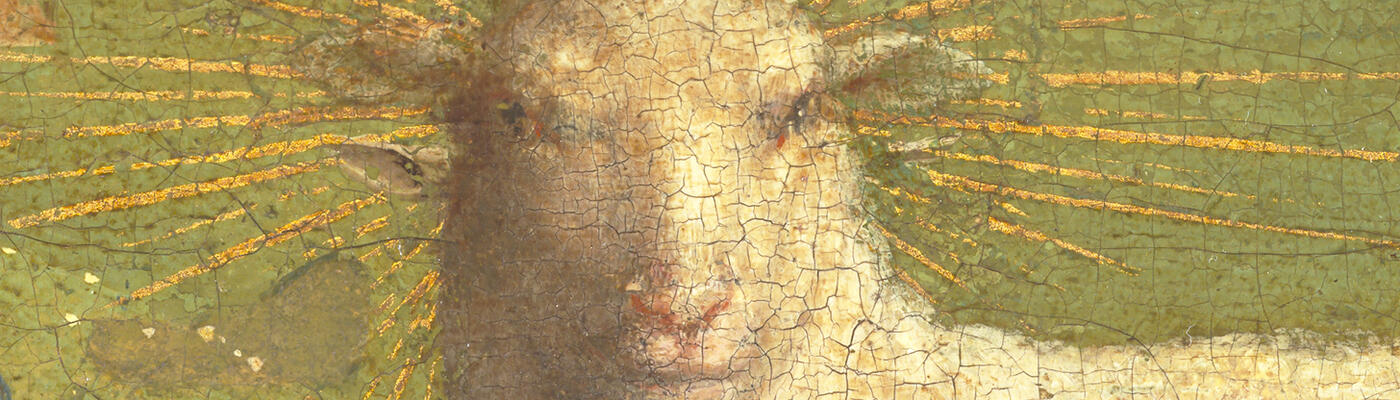

During the French revolution, all religious institutions were disbanded and their possessions confiscated. French troops took the central panel with the adoration of the Mystic Lamb by horse and cart with them to Paris, where it immediately became one of the Louvre’s (then Musée Napoléon) top collection pieces. The side panels remained in the chapter house of the cathedral, where the original Adam and Eve were also stored. After the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, King Louis XVIII returned the central panel. The Ghent Altarpiece was finally back where it belonged. Albeit only for a few months…

Early 19th century: recklessly cut in half

Not one year after the return of the central panel of the Altarpiece to St Bavo's Cathedral, the work was once again dismantled. With the exception of Adam and Eve, on 19 December 1816 the side panels were sold to art trader L. J. Nieuwenhuys for 3000 guilders. Via English collector Solly, they eventually came to be owned by the king of Prussia in 1821. He in turn handed them to the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum in Berlin, where the six wooden side panels of the Ghent Altarpiece were cut in half vertically. A drastic and hazardous intervention aimed to exhibit both sides of the panels at the same time.

1822: fire in the cathedral

Meanwhile, the remaining panels still in St Bavo's Cathedral in Ghent narrowly escaped destruction themselves. In 1822 a fire broke out in the cathedral. In the rush to get the panels to safety, the central panel of the lower register split along its width.

1861: Adam and Eve in pelts

In 1861, the state of Belgium convinced the church administration of St Bavo's Cathedral to sell the original panels featuring naked Adam and Eve to them. The government paid 50,000 Francs for them, and exhibited them at the national museum in Brussels. As part of the deal, the Belgian government donated copies of the wings painted in 1559 by Michiel Coxcie. This replaced the panels exhibited in Berlin at the time. The final part of the agreement had the government pay artist Victor Lagye to paint copies of Adam and Eve. However, with animal skins to hide their nudity. The naked versions had garnered the disapproval of Emperor Joseph II eighty years prior, and likewise were an affront to the Victorian prudishness that prevailed at that time.

1914-1918: bricked into a house wall during the Great War

When Germany invaded Belgium during the Great War, the government feared the confiscation of the Ghent Altarpiece panels. Canon Gabriël Van den Gheyn of St Bavo's Cathedral oversaw the protection of the altarpiece. He did not receive much support, as many feared reprisal by the Germans if they should discover the disappearance of the Ghent Altarpiece. Moreover, there was no more time to move the painting abroad. So the canon came up with a ruse. Van den Gheyn got with two Belgian ministers to draw up a false letter stating that the Ghent Altarpiece was to be transported to England for safekeeping during the war. If the Germans came to collect the polyptych, they would be shown this letter. In reality, Van den Gheyn arranged for the secret transportation of the work in wooden crates to two Ghentish residences, where the panels were bricked into walls and hidden under floorboards. Their ruse worked, and after the war the Treaty of Versailles provided that Germany had to return the panels exhibited at the Berlin museum as part of the war debt. For the first time in over a century, the altarpiece was once again complete!

1934: a bold theft

On the morning of 11 April 1934, Ghent awoke to a serious hangover. Two panels of the Ghent Altarpiece, the Just Judges and John The Baptist, had been stolen from St Bavo's Cathedral! In the empty frames of the altarpiece hung a note stating in French: “Taken from Germany by the Treaty of Versailles”. In the days and weeks that followed, the bishop of Ghent received various blackmail letters in which the sender, calling himself D.U.A., demanded one million Belgian Francs in ransom. To prove that the culprit was actually in the possession of the panels, he led the police to a package in the luggage depot of Brussels-North railway station, where John The Baptist was found. However, the remainder of negotiations failed, and the panel of the Just Judges has never been found.

The bold theft grew into one of the most captivating art robberies of the 20th century.

1940-1944: nearly blown up with dynamite in an Austrian salt mine

During the Second World War, Hitler hatched the idea to turn the city of his youth, Linz, into a ‘Kulturhauptstadt’ (cultural capital) and found a Supermuseum containing all of the world’s greatest works of art. Naturally, he set his sights on the Ghent Altarpiece. The Nazis gathered all of the art they had pillaged from the occupied territories in the Altaussee salt mine in Austria in anticipation of the museum’s construction. When the allied forces approached in 1944, they rigged the mine with large quantities of dynamite. That same year, the order was given to blow up the lot. What could have been one of art history’s greatest disasters was only narrowly averted by the Altaussee residents.

1945: a stormy flight back home

All is well that ends well, one would think. However, the Altarpiece’s journey home was no stroll in the park… On 21 August 1945 the Ghent Altarpiece was returned to Belgium on a chartered cargo aircraft. However, during the flight a heavy storm broke out, and it seemed that the aircraft would not make it to Brussels in one piece. Eventually the pilot managed to put the aircraft safely on the ground at a small military airfield and after a short stay at the Royal Museum in Brussels, the work was finally returned to St Bavo's Cathedral in November 1945.

1950: a cautious conservation and restoration effort

After a few years of calm, the Ghent Altarpiece was dismantled on 23 October 1950 and transferred to the Central Laboratory of Belgian Museums to undergo conservation and restoration under the leadership of Albert Philippot. The campaign was very innovative for its day: restorations were kept to a minimum to respect the historical authenticity and aesthetic of the work. Moreover, the collaboration between restorers, natural scientists and art historians had a major impact on the later development in this sector.

1986: farewell Vijd chapel

In 1986, the Ghent Altarpiece bid its farewell to the Vijd Chapel, the site for which the altarpiece was originally created. For safety and conservation reasons, it was moved to a climate-controlled and heavily secured cage in the Villa chapel.

2012: start of the ultimate restoration of the masterpiece

In 2012, KIK (the royal institute for cultural heritage) began an ambitious restoration campaign of the Ghent Altarpiece. The work would be restored in three phases at the workshop of the Ghent Museum of Fine Arts. Two of these phases have been completed at the start of OMG! Van Eyck was here in 2020.

2021: opening visitors’ centre at St Bavo’s Cathedral

The Ghent Altarpiece is now housed in a new visitors' centre in St Bavo's Cathedral in Ghent.

2022: the restoration continues

The third phase of the restoration begins.

The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb – The return of its divine colours

Discover the extraordinary journey and eventful history of the Ghent Altarpiece. Two brothers retrace the journey of the Ghent Altarpiece and give a fascinating and even surprising insight into the turbulent history of the masterpiece.

The Ghent Altarpiece and Jan Van Eyck

Who was Jan Van Eyck, and what makes the Ghent Altarpiece so special? Discover more on these pages!