The confrontation with Adam and Eve must have been quite shocking in the 15th century. But not for the reason you might think. It has nothing to do with sexuality. Medieval people didn’t have an issue with nudity as such. There are plenty of mythological scenes teeming with naked bodies. But nudity in a Christian context? That was a different story.

Representing biblical figures in the nude was something the 1432 public wasn’t used to.

Of flesh and blood

Representing biblical figures in the nude was something the 1432 public wasn’t used to. Ten years earlier, Masaccio had already painted Adam and Eve naked in Italy, in a fresco in the Santa Maria del Carmine chapel in Florence, but his depiction felt more stylised and less like people of flesh and blood. In the Ghent Altarpiece, they are portrayed at life size in photographic detail. The realism and their enormous presence were probably the most surprising aspects.

Take a look at Adam’s foot stepping out of the frame. This way, Van Eyck creates a direct connection with the spectator’s perspective. The other figures in the upper panels look ahead and remain more distant, but it seems as if Adam is walking towards you. To put this in a modern perspective: back then, this must have felt like the VR effect of someone stepping out of a flat frame. It’s nothing short of impressive.

Adam and Eve, 2.0

The impact of Adam and Eve lingered for a long time, but the nudity in the artwork gradually became a prominent topic. In 1781, Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor, visited Ghent and is rumoured to have been upset by the naked bodies. It is said that the panels were removed afterwards. It may be a rumour, but the emperor was known for his far-reaching religious reforms. And the prudery around nudity in religious contexts had certainly increased by then.

The panels of Adam and Eve were treated quite unfairly for a long time afterwards. In 1816, the exterior panels of the Ghent Altar piece were sold to an art dealer and eventually ended up in Berlin after a few detours. But the panels of Adam and Eve weren’t sold with the other panels. They were the only exterior panels that remained in Ghent, hidden in the cathedral’s archives. In 1861, the Belgian state bought them for 50,000 francs to exhibit them in Brussels.

The bearskins of the 19th century

The idea arose to display the Ghent Altarpiece in its entirety again at St Bavo’s Cathedral, including the exterior panels, but copies had to be used to make this possible. Fortunately, Michiel Coxcie had made an integral copy for the Spanish king in 1558, which could be used perfectly for this purpose. Yet the work was displayed without the nudity, even though the original panels of Adam and Eve were in Ghent.

The church council ordered a copy in which Adam and Eve were dressed from a certain Victor Lagye, a teacher at the Ghent art academy. This is the infamous version with the pelts: Adam and Eve are portrayed on these panels dressed in bearskin underwear. It took until 1920 for the originals to be exhibited once again. We may think this is a funny story, but Facebook’s current policy on nudity isn’t all that different. It seems like we are still stuck in the aftermath or in a revival of this Victorian prudery.

Maximiliaan Martens

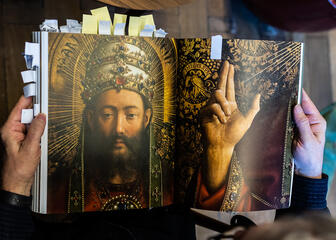

Maximiliaan Martens is professor of Art History at Ghent University and is a world-renowned expert on Van Eyck. Since 2010, he has been heavily involved in the restoration of the Ghent Altarpiece and the expo Van Eyck. An Optical Revolution. He is still fascinated by the topic that interested him in his student days: how can technology and scientific research help us shed new light on the old masters?