Myth busting: 3 persistent fallacies about the Ghent Altarpiece

Right or wrong?

Wrong. The oil-painting technique was already described in a 12th-century treatise. Van Eyck began his painting career much later, around 1420.

Where does this claim come from?

It goes back a long time. Around 1550, Italian art historian Giorgio Vasari wrote a series of artists’ biographies. He claimed that Van Eyck was the inventor of oil paint, in a time when most painters used tempera (pigment dissolved in water and egg yolk). He also called Van Eyck an alchemist, but not because he tried to turn lead into gold. What he meant was someone who was investigating the quality of new substances. In other words, more of a chemist than a magician, and Van Eyck was indeed just that.

Is there a kernel of truth?

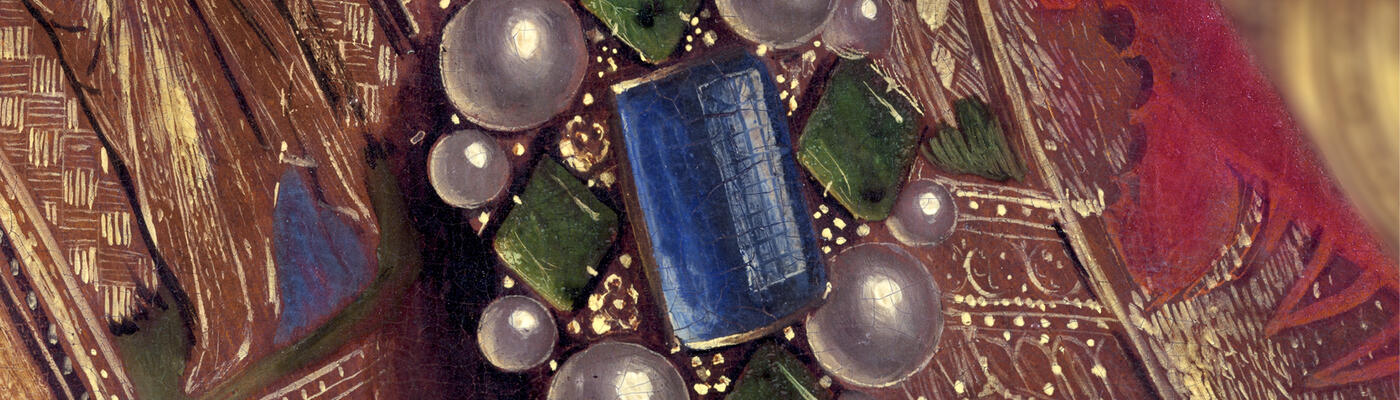

Van Eyck did play an important role in the refinement of the oil-painting technique. Oil dries a lot more slowly than water, but by using new drying agents, for instance made from nuts, Van Eyck succeeded in accelerating this process. Thanks to the new siccatives, he could work more quickly and do what he could do best: capture the quality of light perfectly in thin overlying layers of paint. And I consider this a revolution in the history of painting.

Right or wrong?

Wrong.

Where does this claim come from?

This is a widespread myth, recently repeated in issue 351 of the comic series Suske en Wiske. Jan Van Eyck did make several journeys on behalf of Duke Philip the Good. In 1428, he was part of a delegation that travelled to Lisbon to negotiate a marriage between the Duke of Burgundy and Isabella of Portugal. There, Van Eyck painted her portrait and had it sent to Philip by courier, so that the Duke could see whom he was to marry. He must have liked what he saw, because Isabella became his third wife. Unfortunately, the portrait itself has been lost.

Is there a kernel of truth?

Jan Van Eyck was on the payroll of the Burgundian court. Duke Philip even gave Van Eyck a considerable pay rise when the latter threatened to seek employment elsewhere. But he was employed as a painter, not as a diplomat, and he certainly wasn’t a spy.

Right or wrong?

Wrong, unless you know more.

Where does this claim come from?

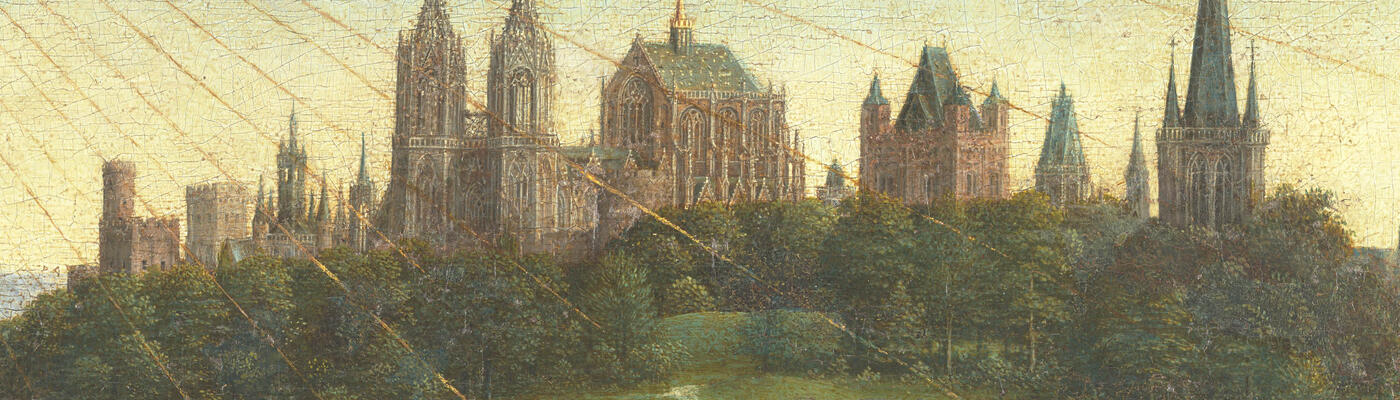

In the night of 10 to 11 April 1934, the panel of the Just Judges was stolen from St Bavo's Cathedral, together with the rear panel of John the Baptist. The latter panel was found in a locker at the Brussels-North railway station, together with a note demanding more money. But that's where the trail came to an end. Numerous colourful details, including blackmail letters and a deathbed scene surround this spectacular theft.

Is there a kernel of truth?

None whatsoever. Anyone who has a theory about the whereabouts of the missing panel is heard. There have been searches and excavations in the Castle of the Counts, a well, a parking garage, a French monastery and private homes. Not long ago, the street was broken up at Kalandeberg, in the centre of Ghent, with journalists and photographers standing by. The only reason why I hope they find the panel, is that the discussion will then be closed.

Jan Dumolyn is professor of medieval history at Ghent University. As co-curator of Van Eyck — An optical revolution he re-examined the historical sources relating to the Van Eyck brothers. That was high time, because (too) many myths and half truths about the Ghent Altarpiece are endlessly repeated.