So precious and so fragile: ultramarine

When painting certain areas blue, Van Eyck used ultramarine. It was made from lapis lazuli, a blue rock that had to be brought here from Afghanistan via Italy. The name ultra-marine also literally means ‘from overseas’. To prepare the pigment, Hubert's and Jan's assistants had to grind and filter the tiny pebbles, until only the purest blue was left. That whole process made ultramarine incredibly expensive – the pure pigment was even more precious than gold.

Unfortunately, ultramarine is also prone to ultramarine disease: a degradation of its colour, especially in the darkest sections that consist of the pure pigment. The blue colour gradually turns greyish and dull. This gives rise to a weird effect, because the shadows become almost lighter than the rest and the contrast disappears altogether. Ultramarine disease is irreversible, but with careful retouching, you can restore the volume and bring it closer to its potential. In the case of a prophet on the centre panel, this worked out very well and in the case of the Virgin's monumental blue robe, which we are currently working on, we are expecting a similar result.

The fashion of the day

When working on the conservation of a panel, the first big sense of relief is felt when you remove the yellowed layers of varnish. It means that everything can breathe and come back to life again. In fact, it was no different in the past: all that the people who overpainted The Ghent Altarpiece in the sixteenth century wanted to do was revitalise the dull colours. But back then, they simply painted on top of the darkened varnish layers instead of removing them. And sometimes, they took extra liberties in the process.

You should know: the job of conservator did not exist in the past. The people who overpainted The Ghent Altarpiece in the sixteenth century were painters themselves. For the most part, they remained true to Van Eyck's composition when repainting, but in the robes, it is notable that they often simplified the folds and made the folds in the fabric ‘softer’, according to the taste at that time. You can see this clearly in the robe of the angel Gabriel, for example. Van Eyck's original is more contrasting, with sharp, strongly defined folds.

Applied brocade – the biggest challenge?

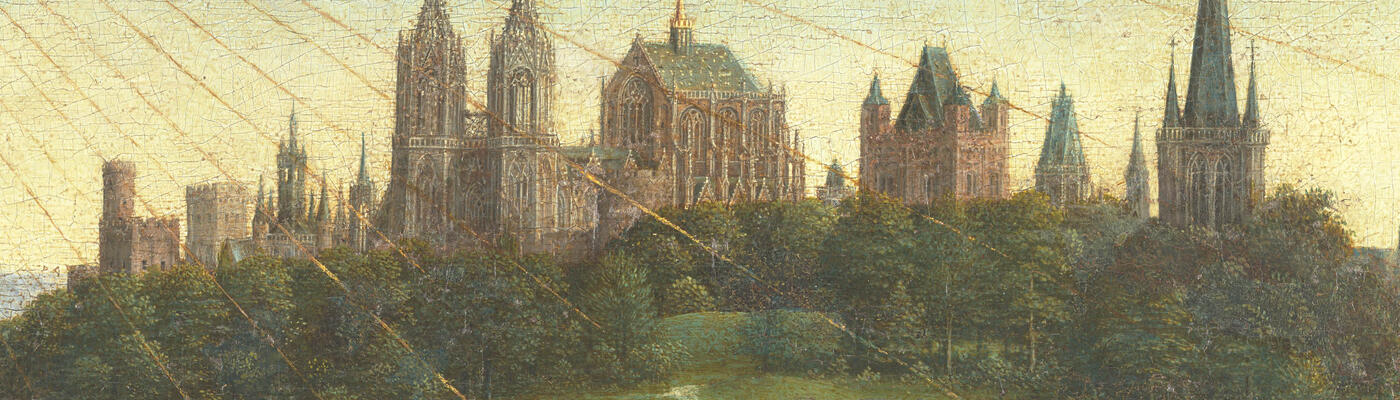

In the final phase of the conservation project, we are tackling the upper panels of the opened altarpiece, with Adam and Eve, the singing and music-making angels and the three enthroned figures. What makes those middle figures so different from the previous panels are the ‘applied brocades’ in the cloths of honour behind them. Applied brocade is a sophisticated form of textile imitation for which Van Eyck used reliefs of tin foil, which were gilded and painted. That underlying foil has oxidised over time and is very fragmented, which makes treating the applied brocades quite a feat.

The work on the applied brocades is now in full swing, so I am very curious to see the extent to which we will be able to conserve them. The tiled floors are also exciting. If we can remove the overpaintings there, the results could be spectacular. Van Eyck painted the original with transparent layers of paint on top of silver and gold foil, so it would be very nice if we could restore that effect in all its glory as well.

Kathleen Froyen

The conservator Kathleen Froyen has been working full-time on The Ghent Altarpiece since 2018. She coordinates the conservation studio at the Museum of Fine Arts and sits on many steering committees and advisory committees, but most of all, she enjoys getting behind the microscope herself to do some real work: the conservation of Van Eyck's magnum opus.